How does a person learn new motor skills?

A person learns his first motor skills before he is born, and after entering the world, this process accelerates tremendously, just like all other learning. Babies, toddlers and young children are like sponges, absorbing information and skills from their environment and trying to apply these with varying success, linking them to already learned entities. For example, a child learning to walk persistently tries to maintain his balance, and every stumble corrects the performance towards the correct implementation. It is worth noting that the child does not need actual verbal or even repeated visual instruction, but the learning process is self-reinforcing. Of course, the encouragement, help and possible reward of proud parents speed up learning.

Simplified, the learning process is largely the same, whether it's learning to walk or the technique of a roundhouse kick.

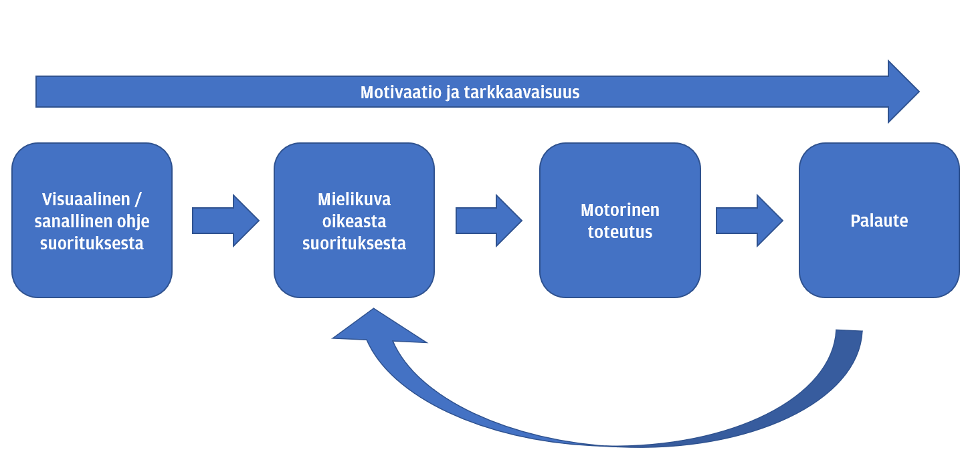

First of all, the learner needs some kind of visual, verbal or a combination of these models of motor performance. A child learning to walk has been watching his parents' recording for a long time, and the motivation to be able to do the same himself is obvious. Movement speeds up considerably, it is easier to reach to grasp things, and parents clearly get excited about companies. An enthusiast practicing the round kick, on the other hand, receives verbal instructions from the coach on the different phases and execution of the kick. Almost without exception, a visual model of the finished kick also follows the narration. The hobbyist's attentiveness and motivation to learn new skills significantly speed up or slow down the learning of the skill. The coach and the operating environment are very decisive in this regard.

Already during the model, an outline of the performance is formed in the learner's mind and the nervous system that controls the movement trajectories in question is activated. When learning new skills, new nerve connections are created in the brain, and at the same time, the entity being learned is linked to something already learned. For example, a spin kick is much the same as a front kick, in which case the nerves created with the already learned skill also help in learning the next skill. The impersonation phase is largely unconscious processing, but directing attention and concentration to the subject to be learned will of course greatly accelerate learning, while a weakening of attention hinders learning. A child learning to walk will fall if the working memory is overloaded, e.g. with stimuli from a nearby TV, just as the performance of a learner of a round kick is disrupted if he thinks about the next drink break during the learning phase.

After the brain and nervous system have been worked on the performance of some kind of model, the learner tries it in practice. Small children are constantly doing experiments on how the body behaves and how, for example, shifting the center of gravity affects balance. Similarly, the learner of the round kick may impatiently try the performance a few times while still being instructed by the coach. The most essential stage of all learning, especially motor skills, is doing it yourself. Learning the roundhouse kick by reading the steps of the technique in a book, for example, is quite challenging, although not impossible. For example, imagery training is based on this. In this case, the actual making phase is left out and the training is based entirely on mental images and creating nerve connections through this.

After the motor performance, the learner receives immediate feedback from his body about the quality of the performance. A small child learning to walk notices the effects when he stumbles and automatically corrects the performance on the next attempt. Similarly, the learner of the spin kick immediately notices how the kick feels and in which direction the foot ends up in the end. A learner in the early stages of learning is not yet able to grasp bodily feedback very well or understand how it affects the quality of performance. Through practice and repetitions, self-reflection skills develop and the learner is more and more able to visualize the entirety of their performance, possible shortcomings and various variations. Feedback on the performance is of course also given by the coach and peers.

The learner combines the feedback in his mind into a new model of the correct performance and the cycle starts over. This is how the skill develops through a cycle formed by repetitions and feedback. The neural connections and the physical characteristics needed to perform the skill develop, making the performance constantly easier and more automatic to repeat. In the initial phase of training the spin kick, the learner still has to focus on each sub-component of the kick separately and a large part of the working memory has to be reserved for the performance itself. On the other hand, an enthusiast who has performed thousands of spin kicks knows the execution almost automatically in different versions and is able to combine it with other learned entities, for example a match movement or part of kick sequences. Top athletes make what they do look effortless and easy, even in fast situations. Performances have been trained to be so automatic and nerve connections so strong that significantly more performance capacity is saved for other functions.

Learning motor skills is most intense in childhood, but even as an adult, you can acquire new skills, albeit more slowly. For this reason, children should practice as versatile as possible various physical skills when the sensitivity season is at its peak.

Learning physical skills is always a social process

Almost all learning is always more or less a social activity, and especially in the early stages of learning, the role of the environment and the teacher is emphasized. Phenomenological learning, problem solving, exploratory learning and task-based learning have been strong trends in the pedagogical discussion in recent decades, and their methods have been applied a lot in physical education and sports. The main idea is that the responsibility for learning is transferred more and more to the learner himself and the learning methods are more and more about doing things instead of passive information transfer. However, it is essential that the learner is not immediately thrown into the deep end without support or tools with which learning can be taught in general. For example. reflecting on different applications of the roundhouse kick in small groups can be a good learning task, but the results will be poor if the actual roundhouse kick practice is still at a stage. Learners are not able to connect the skill they are still practicing with other entities or to understand variability in performance methods.

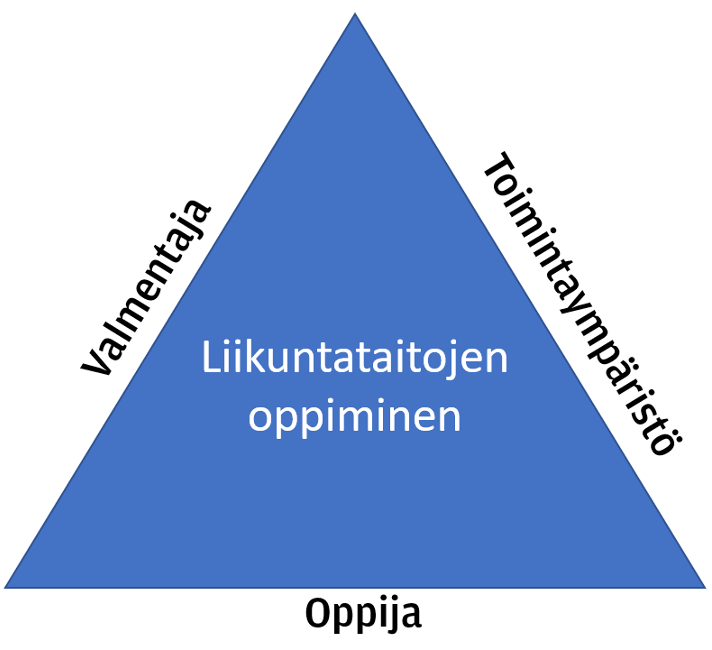

The coach, the learner and the operating environment form a whole, the center of which are the physical skills to be learned.

All factors of the triangle have varying degrees of influence in different situations. For example, a young novice hobbyist needs considerably more support from a coach in learning a new skill than an experienced adult hobbyist. Correspondingly, a beginner needs a clear and learning-supportive operating environment, while a conker can do an independent and learning-supportive exercise even at home with the guidance of a coach.

The learner himself affects the outcome of the learning process by directing his attentiveness and concentration to the teaching and the performance itself. Learning is facilitated by an active and curious attitude towards the learned skill and the operating environment. This can be seen, for example, in asking additional questions to the coach and in active communication with training buddies. you can get much more out of the exercise when the learner consciously puts himself in a receptive and open state of mind.

The operating environment includes e.g. training space, training equipment and training buddies. A good space enables versatile exercises and does not in itself limit the coach's toolbox. Good space can also be limited or expanded as needed. The comprehensive training equipment gives more options for the implementation of the exercises and helps in directing the attention and finding the right ways of performing the exercises. For example, a child practicing a spin kick may understand the trajectory of the technique much better when he has a kick target to direct his attention to. Correspondingly, training buddies and peers contribute to the learning of sports skills when everyone has a positive attitude towards the teaching situation and the subject to be learned.

The coach is responsible for planning the exercise and directing the implementation. The above-mentioned learners and the operating environment serve as boundary conditions for the exercise. The core competence of a trainer is the ability to identify the starting level of the learners or the group and plan the exercise so that it serves their learning goals best. The challenge here is of course the individual differences within the training group.

The exercises should be sufficiently challenging, in which case new nerve connections are created and the skills to be learned are linked to larger entities. Too easy and monotonous practice leads to so-called overlearning, i.e. the practice no longer improves marginally and does not increase the ability to apply the skill in new situations. Instead, exercises that are too difficult eat away at learners' motivation when the skill does not seem possible in light of current knowledge. The best results are achieved when easy and difficult exercises are mixed within a single exercise, and not always linearly from easy to difficult. For example, a round kick exercise can be planned so that always after the technique period, the skill of kicking is tried to be applied as part of a more difficult whole, such as a match technique from a movement. After this, we return to the technique phase with a slightly new perspective.

A coach's professionalism also includes knowing the special features of their own sport and the ability to apply different teaching styles to best serve the learning goals.

Special features of taekwondo as exercise and sports hobby

The rules and technical requirements of the sport form the boundary conditions of training and thereby a unique training culture within the sport. At the grassroots level, training cultures can of course vary widely, for example between clubs or coaches who teach in different styles.

Taekwondo's sport requirements form a very broad and open field of action. Only one club may practice:

- Basic techniques

- Business series

- Kick technique

- Match Taekwondo

- Crushing

- Self defense skills

- Acrobatics and freestyle moves

- General physical skills

- Wide variety of physical properties

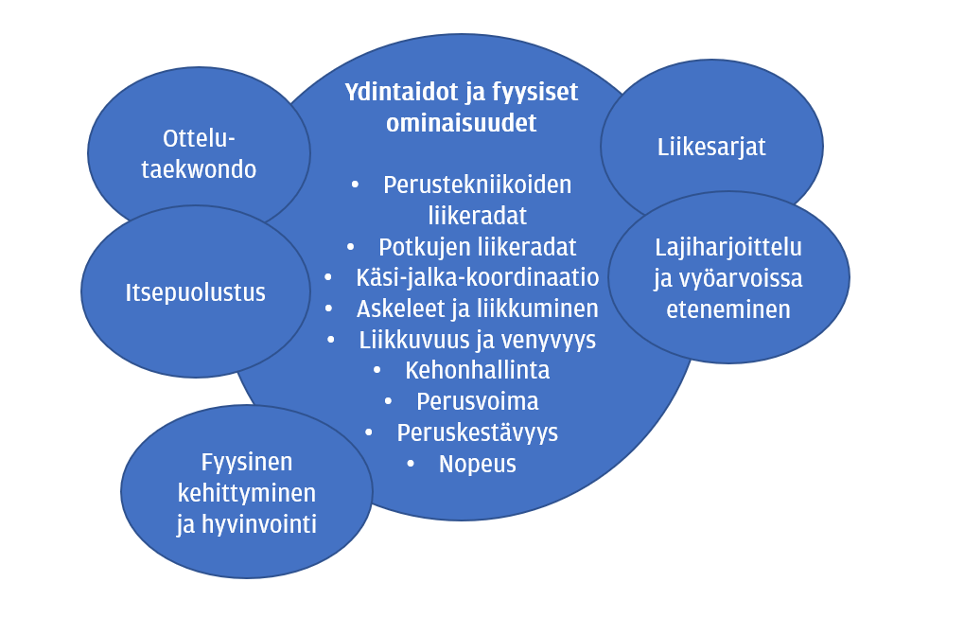

Versatility should be seen more as an opportunity than a threat, although sometimes the scope of the sport and the abundance of teaching topics may cause a headache. It is essential to understand that the wide environment provides a basis through which specialization in, for example, competitive matches is implemented. Almost without exception, the best results are achieved through late specialization by providing a varied and stimulating base and emphasizing specialization at a later age. Taekwondo allows late specialization very well. The spectrum of basic skills and physical characteristics to be practiced is so wide that side sports are not needed alongside, although this is not a disadvantage either. Children and young people should be trained in all aspects of the sport and encouraged to compete in both forms of competition, if competing at all motivates the enthusiast. At the junior age, you can already start to shift the emphasis to, for example, more intensive competition training, but on the condition that the basic training has been done with sufficient care.

The whole can be understood by thinking of basic skills and physical characteristics as the center of core training and specialization as part of this whole. The image is an illustration and does not depict the complex entity as such.

Different teaching styles in taekwondo

The teaching style describes the implementation methods chosen by the coach in carrying out the exercise. Roughly different teaching styles can be compared, e.g. based on whether the focus of the activity is the coach, the learner or perhaps the operating environment and social context. The traditional teaching model in both the school and sports worlds has been to favor teacher-led styles, where the role of the coach or teacher is central and the learners are in a relatively passive role of receiver. Taekwondo is no exception in this regard. In a traditional taekwondo exercise, the coach shows the models, gives instructions and then calls out the pace in command style while the learners perform the techniques in unison. In the more applicable parts, the coach defines in advance how the application will be implemented and the trainees try to complete it according to the model.

the good side of coach-oriented teaching styles is that they help the operating environment and the implementation of the exercise to roll in a controlled manner and according to the plan. In addition, the learners receive ready-made models and tools that enable independent completion and application of the skill later on. Because of this, coach-led teaching styles are particularly suitable for teaching elementary groups and children's training groups.

However, a strong coach-led approach has the disadvantage that it does not fully take into account the learners' individual differences, starting levels or self-regulation skills. Faster and more skilled students are not able to move to more challenging performances, while weaker ones may fall off the sled. Correspondingly, the learners' independent thinking and skill-related application ability may remain on a thin foundation, and in the extreme learning and performance of the skill are mainly linked to the coach, instructions and external rhythm. For example, a competitor trained with a command style may find that he is unable to perform a well-practiced solution model in the competition when the context changes from a familiar environment to a different one.

Learner-oriented teaching styles, on the other hand, start from the idea that learners are ultimately always responsible for their own learning and that the most effective way to learn is by experimenting and doing. In learner-oriented teaching, many different tasks and problem solving are used, in which case the learners have to make choices and solutions themselves.

The good side of learner-oriented teaching styles is that they develop creative problem solving and the ability to apply learned skills in very varied situations. The coach also has better opportunities to take the skill level of the group members into account and, if necessary, give more support to those who need it. Those who learn faster, on the other hand, are able to move more efficiently to more challenging tasks.

The biggest challenges, on the other hand, are related to the fact that learners' self-regulation skills or basic knowledge are not necessarily sufficient for working independently with the given goals. In this case, teaching results remain poor and learners have genuine challenges to reach the next level of development independently. It is also significantly more difficult to plan learner-oriented exercises so that the intensity remains hard throughout the exercise. Hard training is not an end in itself, but sometimes, for example, a fighter doing creative situational training also needs training where the pace comes from the outside and the performances are done hard, a lot and they are simple enough.

It is worth remembering that no teaching style is purely coach- or learner-oriented, but actors are always present with different emphases. In terms of teaching styles, it is also not worth looking for the Holy Grail, which would be the one correct way to teach sports skills. The most important thing is to understand the starting level of the group, the differences between individuals and the boundary conditions of the operating environment and shape the exercise based on these. A versatile and self-critical coach is able to test different styles with different groups and find the most optimal ones for different situations. He also remains open to new ideas and is basically ready to take the learners into account, even if the exercise is very teacher-led or command-style. He is also able to offer concrete tools with which to progress in the learned skill to the next level or application phase.

In the following table, the most commonly used teaching styles have been compiled and an example exercise has been given for all of them.

|

Teaching style |

At the center of teaching |

Activity and goal |

Example exercise |

|

Command-style teaching |

Coach |

The coach shows and explains the instructions to everyone together. The assignments are usually done at the same time at the teacher's command. The feedback is mainly shared and concerns the entire group. It only takes a little space and is the most effective way to keep the group under control. The learner's role is very small. |

In the form of basic technology training. The director shouts the commands. |

|

Task teaching and differentiating teaching |

Coach |

The coach gives either joint instructions or separate instructions to different small groups, after which the assigned task is practiced at one's own pace. The coach gives feedback to both the group and individuals. Tasks can be effectively differentiated with exercise equipment. The trainer can assign different difficulty levels and progressions to the tasks. |

Situational training in match training. Let's practice a prepared situation where A kicks with the back foot and B does a back kick in response. We take turns at our own pace. The coach goes around giving feedback and additional instructions. |

|

Teaching based on self-assessment |

Learner |

The coach gives the task, but the learner's task is to independently evaluate his performance. The coach must give clear instructions on the evaluation criteria so that the learner has enough tools to correct his own performance. The coach can still be involved in giving feedback. |

Complete sets of movements are practiced so that the coach always gives an instruction between the exercises, what to pay attention to. Learners evaluate their own performance and do it at their own pace. |

|

Guided insight and problem solving |

Learner |

The coach gives the students a problem or a task, but not a direct solution to it. Most of the time there are many solutions and the learner has to think about the implementation method himself. The coach can guide insight with help questions and tips if necessary. The tools can effectively limit problems. |

Situational training in match training. The coach assigns A the task of attacking only with front leg spin kicks, and B must develop different defensive solutions for this. |

|

Teaching based on creativity |

Learner |

The coach gives a task where the learners have to develop something new independently or in small groups based on the skills they have already learned. The coach gives the framework for the task, but otherwise the work is free and the emphasis is on the creative application of learned things and the development of new ones. |

The children's group is divided into small groups. The groups independently develop a short taekwondo performance. The task can be limited to certain elements or you can freely develop the display according to your own taste. |

|

Pair or group guidance |

Learners together |

The coach gives the task or its main features, after which it is practiced in pairs or groups so that others are constantly given feedback and the learners are each other's peer teachers. The exercise can also be based on making the students themselves teachers. |

Movement series training in pairs or small groups. One performs the performance and the others give feedback either according to the coach's instructions or independently. |

|

Teaching by example (coach included) |

Coach and learner |

The coach gives a task, after which you do it yourself in pairs or in small groups. The coach must be able to achieve the performances that are hoped to be achieved with the learners. The feedback is very individual, but it is difficult to monitor the activities of the entire group. |

Circuit sparring, where the coach is involved in doing it himself. He always gives individual feedback to whoever he is paired with. |

It is therefore worth testing different styles in your own coaching work and honestly evaluating their impact on learning. Even within a single exercise, you can vary from one style to another, and often this is the most effective way to learn something new and apply what you have already learned.