What actually causes the competitive tension?

Excitement is certainly a familiar feeling for every athlete, and almost everyone will certainly agree that exasperation does not feel very pleasant. Experiencing excitement and especially reactions and ways of acting vary greatly between individuals. Others are in an overloaded state, unable to stay still for a moment while the other goes limp and the muscles feel heavy. However, it is good to remember that tension is also a good thing for performance, and it is precisely through the tension reaction that the body optimally prepares for performance.

Excitement is a completely natural reaction to a perceived threatening situation. Tension is triggered by a stress reaction, which in turn arises from the fact that we subconsciously interpret that we are in a threatening or dangerous situation. This defense reaction is older than our species and has also been a key survival mechanism for most of modern man's time on earth.

Usually, when examining the phenomenon, we talk about the body's automaticity fight or flight -reaction, the task of which is to automatically and quickly prepare the body for a situation where we have to work at the limits of our abilities. Quick action, for example when a tiger is lurking in a nearby bush, has helped our species survive harsh conditions where dangers are commonplace. Today, we don't have to fear spontaneous attacks from tigers, but our reaction to perceived threatening situations is completely identical to our ancestors.

The stress reaction triggers a spike in cortisol and adrenaline in the body, which in turn direct the nervous system to focus all of our essential resources on activities that help survival. This means, for example, an increase in blood circulation around large muscles and in the areas that control reactivity and perception of the brain. Our heart rate increases, our blood pressure rises and our breathing becomes more rapid. On the other hand, functions secondary to survival, such as digestion or areas that control the more analytical parts of the brain, slow down. Because of this, e.g. on race days, the stomach is often a bit upset and the food doesn't taste good. The thought also doesn't really want to run, which is often reflected in the fact that we forget things and entities during competition performance that we control well in indoor conditions. They just aren't ingrained enough to be automatic functions.

The tension in the races is therefore caused by the fact that you subconsciously interpret the situation as threatening, even though you rationally understand that nothing terrible can happen. However, the reaction is so automatic that you can't just force your body not to tense up, and there's no reason to. As said, the right amount of tension improves the level of performance.

The intensity of tension is especially affected by how we handle the situation and what kind of thought chains it generates. With the help of these, we can also learn to regulate the amount of our tension through training and thereby optimize our competitive mood.

How much is an appropriate amount of tension?

In a stress reaction and state of tension, our body prepares for the performance and competition situation, and trying to get rid of all tension would be a bad solution when thinking about the competition performance. The essential thing is to find the means that suit you, with which you can regulate the amount of tension and feeling so that when the competition comes, you can perform at your best.

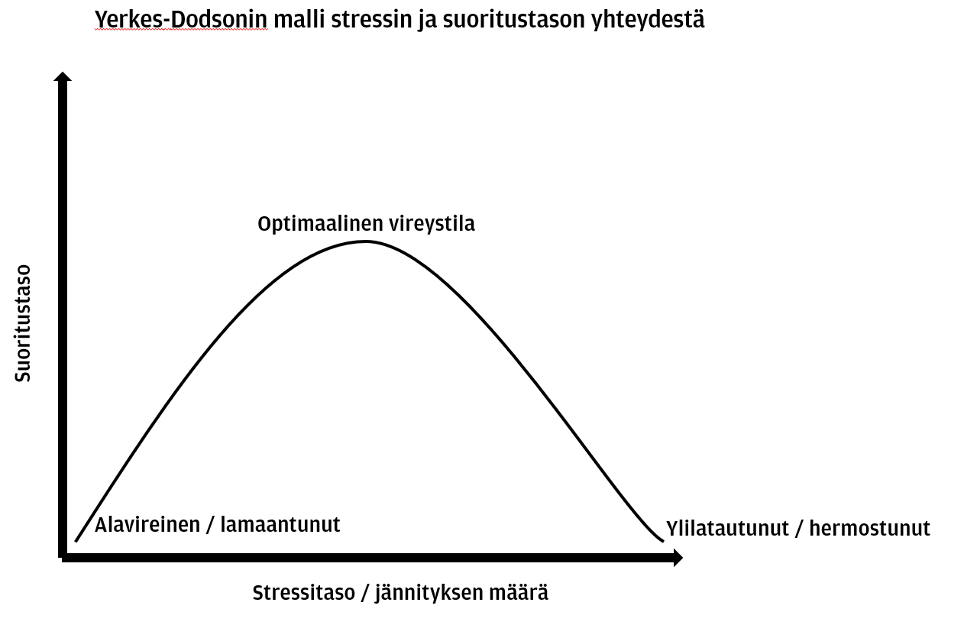

The Yerkes-Dodson law describes the connection between the state of stress and the level of performance and was developed already at the beginning of the 20th century by psychologists Robert Yerkes and John Dodson. The model is, of course, a simplification of complex processes, but it has stood the test of time and also illustrates well how to find the optimal state of alertness needed for sports performance.

It is good for the athlete to learn to observe and understand where his stress level usually settles on the day of the competition and what kind of feelings and thought chains arise from it.

For some, the stress level and the amount of tension grow so big that they start to hinder performance. This can be seen as restlessness and difficulty concentrating on things that are essential for performance. Athletes often try to relieve tension with familiar emotion regulation methods. One immerses himself in listening to music that helps the body and mind to calm down, while the other has a compulsive need to warm up all the time and keep the body moving.

For others, the rise in stress levels causes the opposite reaction, i.e. the body starts to feel heavy and depressed. The body goes into an economizing flame, as it were, and lowers the stress level mechanically if it is not able to do so at the level of thoughts. In this case, the athlete should find ways to raise the state of alertness, for example by means of a sharp warm-up.

Learn to recognize your own stress reactions

When it comes to regulating tension, it is essential to first learn to recognize your own standard reactions to a situation perceived as stressful. It's worth starting by considering how tension changes your actions on a mental level, as bodily reactions or changes in behavior.

Mental level (cognitive changes)

- Thought chains - what kind of thought chains does excitement create in you. for example, do you go over and over the possible outcomes or mistakes you might make. Do you think a lot about what others think about your performance or result?

- Emotional states - What kind of emotional states does race day and race performance cause in you. For example, do you feel scared or maybe excited?

- Attention and ability to concentrate - Can you focus on things that are essential for performance. Where is your attention directed and what kinds of things do you notice in particular?

- Self-talk - What is your self-talk like on race day? Do you repeat positive sentences to yourself in your mind that help you perform, or is your self-talk more discouraging and preparing yourself for failure in advance?

Bodily reactions (somatic changes)

- Sensations in the muscles - Do your muscles feel stiff and heavy or do you feel light and fast?

- Increased heart rate and breathing - Monitor your breathing and heart rate

- Butterflies in the stomach – A feeling of pressure in the lower abdomen and perhaps an increased need to go to the bathroom.

Changes in behavior

- Posture and gaze - Does your posture change when you tense up? Do your shoulders slump or do you look down at the floor?

- Activity Rate – Does stress increase or decrease your activity? Do you feel like you should be doing something all the time or rather that it would be nice to curl up for a nap?

- Introversion and extroversion – Do you have more or less contact with other people on race day? For others, the support of a group can be important when they are tense, where the other would like to be more at peace.

So many changes take place in the mind and body of the athlete as they prepare for the performance. Some are easier to notice than others, and the whole they form is unique to each athlete. Recognizing your own stress reactions is a useful skill, because only through them can we regulate our overall mood through training.

How do I regulate my own state of alertness?

It would be nice if we could click our fingers to put our bodies in the perfect state of tune for performance. However, this magic trick is not possible, and even top-level professionals have to constantly practice adjusting their tuning. Peaks are also exciting, even if it doesn't always seem so from the outside. However, through experience and purposeful training, they have learned to utilize their stress reaction as part of preparing for competition performance.

Next, we will introduce ways in which you can regulate your level of alertness and tension, but as said, purposeful training of these even outside of competition is the only way to make them part of your toolbox.

Train and compete a lot and a little more

This instruction is pretty self-explanatory. By doing something repeatedly in large quantities, it develops into a routine, and routines are easy to perform, no matter what the state of alertness. It is clear that someone who goes to 40 competitions a year feels the competition situation much more familiar than someone who goes to six competitions. Similarly, self-confidence in competitions is born above all from the feeling that you have trained hard and done everything you can in the gym.

Learn to recognize and name your feelings during the race day

As mentioned earlier, recognizing our own sensations and bodily changes is necessary if we want to regulate them. Naming sensations (labelling) is already a strong tool for self-regulation. The mere fact that we are able to tell ourselves honestly that we are tense at the moment and it feels like this and that helps us to get rid of all the chains of thought and judgments that we automatically attach to the situation.

One effective way to relieve tension is to redefine the sensations it causes as excitement. Physically, these sensations are almost identical, so through self-talk we can, as it were, "trick" ourselves into feeling enthusiasm instead of tension.

Learn to turn negative thought chains and self-talk into positive ones

No matter what our external situation is, our mind tries to structure it in some way in an understandable and controllable form. When a tiger attacks from the mouth, we don't have time for long chains of thought, so we act purely through the stress reaction and automatic functions. However, in a prolonged stressful situation, for example when waiting for our own performance, we have time to reflect on the situation.

However, our thought processes are often unreasonably negative, as is our self-talk. In a threatening situation, our mind prepares for the worst possible outcome, so that it would be easier to accept it in time. However, negative thought chains hinder the competition performance itself and take our attention to things that are beyond our control. In addition, focusing on the negative, e.g. avoiding mistakes, will almost certainly lead to exactly this mistake. For example, if you shout to the opponent in the middle of the match not to look at the scoreboard, he will almost certainly immediately turn his eyes there.

To break negative thought chains, it is enough to be able to recognize them (when they appear) and accept them as they are. In this case, their power ceases automatically. It is also worth learning a few positive self-talk patterns, which are repeated like a mantra, e.g. right before the performance:

"I have practiced hard and I can do this"

"I feel strong" (even though it doesn't feel like it)

"The first thing I do in my performance is..."

"I have prepared sufficiently. We'll see how long it takes this time"

"The only thing I can influence is my own performance"

Focus on things you can influence

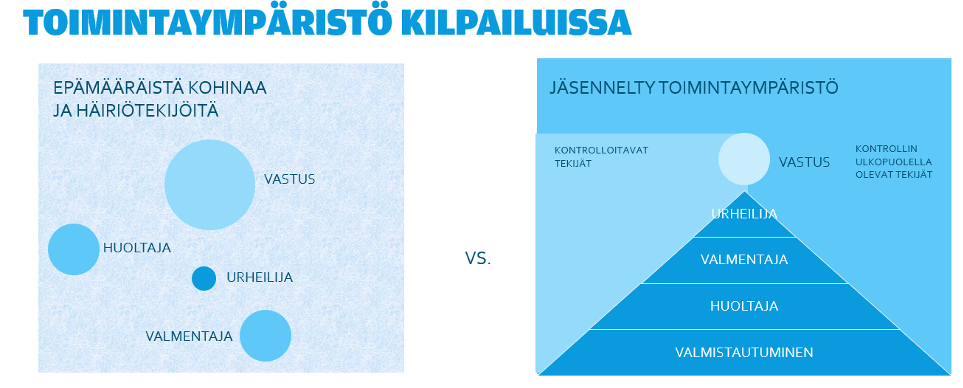

Every extra thing that the athlete pays attention to during the competition day is taken away from the resources that he could use for things that are essential for performance. For example, a movement series athlete preparing for his own performance has no reason to intensely watch the performance of his opponents, because they simply cannot be influenced. At worst, they only increase our own anxiety if we evaluate the opponent's performance as good. Correspondingly, when a competitor focuses his attention solely on the characteristics and skills of his opponent, his own performance suffers.

The athlete should develop a basic routine that suits him from race to race, consisting of things that are controllable and not dependent on changing external factors. There will certainly be changes and surprising situations in every competition, but a good basic routine takes these into account. These include, for example, eating on race day, planned warm-up and finishing just before the performance.

Mental preparation:

Almost all top athletes prepare for competition in one way or another, also psychologically. At the very least, you should go through the competition situation in your mind as a process a few times before the event itself. Imagine the whole day in your mind as visually and step-rich as possible. What kind of competition venue is it, how do you warm up, what do you eat at any point, what kind of sensations do you get during the day, how do you feel right before the performance, etc. In this way, it is possible to collect a "competition routine" even when we are not in competitions. Going through the situation intensively in the mind triggers the same mechanisms in our body as the situation itself.

Mental preparation can also be taken much further by making imagery training a regular part of your training routine. In this case, the athlete practices the control of the body's self-regulation mechanisms in advance, and ready-made routines can be created, which can be used to tune in to the optimal state in the blink of an eye before the competition performance. However, you should start practicing these with the guidance of a competent trainer.

Correspondingly, different breathing techniques and mindfulness -exercises regularly gives you new tools for managing bodily and mental sensations.

Something to remember

- Tension is a completely natural reaction to a perceived threat, and the right amount of tension improves performance.

- Learn to recognize how tension affects you mentally, physically and at the level of behavioral changes.

- Develop routines for yourself that you can repeat from competition to competition, even if external factors change.

- Train and compete hard to build up your routine.